Author: Bill Ward

A couple of years ago, Ysmael Espinosa of Medina Garden Nursery and I were discussing the sparse occurrence of big red sage (Salvia pentstemonoides) in the wild. He said he thought he had seen a couple of big red sages several years ago when he was canoeing on the Guadalupe River upstream from Ingram. Wow! As far as I know, that species of Salvia never has been reported on the Guadalupe River!

Ysmael probably rues the day he told me about his sighting, because for the next two years I kept bugging him about revisiting that locality. One night last August, he called to say he had checked out the site that day, and yes, there were indeed two or three plants of Salvia pentstemonoides blooming along the river.

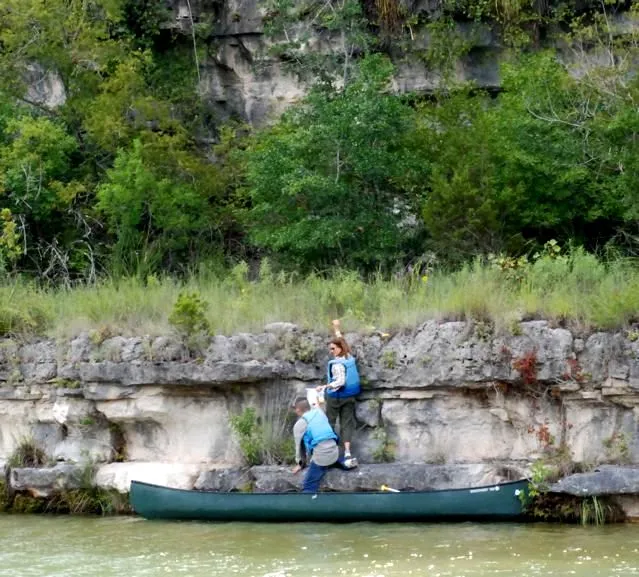

A few days later, Ysmael led a small group of us to see his discovery. A few large plants of big red sage were growing out of the eight-foot-high limestone bluff along the river. Wow again!

The last time this species had been recorded in Kerr County was in 1943 in Turtle Creek south of Kerrville. That was the last known occurrence in Texas before big red sage was thought to have gone extinct in the wild. It wasn’t seen again until the early 1980s when Marshall Enquist identified Salvia pentstemonoides in Bandera County.

Above the bluff along the Guadalupe River was a wide ledge that extended tens of feet back to a very high cliff. Our curiosity got the better of us, and we climbed up to see what was growing on the ledge.

What we found was one of the largest known wild populations of big red sage! The total number of stalked plants and rosettes at the Guadalupe River site is about the same as that of the big red population Patty Leslie Pasztor spotted six years ago when she and I were kayaking through limestone canyons on Cibolo Creek.

The plants we counted on the Guadalupe River increased the number of known big red sage in the wild by nearly 65%. Today big red sage is known in only four Texas counties: Kendall, Kerr, Bandera, and Real. Kendall County has about 60% of the total.

The total number of known wild big red sage plants in Texas is less than 450, making this salvia one of the rarest of our native plants. Even so, there are no legal protections whatsoever for Salvia pentstemonoides. Landowners need have no fear of reporting newly discovered populations of big red sage. The presence of big red sage on a property brings no restrictions of any kind.

Salvia pentstemonoides is not in danger of going extinct, because so many gardeners raise the plant. However, the few wild populations and low total numbers of individual plants mean that this species in the wild probably cannot easily survive the increasing loss of habitat and decline of springs in the Hill Country. Could big red sage soon become extinct in the wild?

Less than 15 years ago, the largest population of big red sage in Texas was under the I-10 bridge over Frederick Creek at Boerne. Because of the 1997 high stand of flood waters, encroachment of exotic plants, and heavy browsing by domestic and exotic deer, there are no survivors at that site today.

I’m optimistic that the number of big red sage in the wild is larger than we think. After all, about 98% of today’s known population of big red sage was discovered since 2004. This gives me hope that there are lots more stands of big red sage to find.

Most of the extant big red sages are growing in intermittently moist, steep-walled limestone canyons in spots where the plants are not accessible to browsing animals. Many of these sites also are not accessible to a lot of human traffic. Who knows how many big red sages are hidden away in Hill Country canyons?